Jeff Hersch is the Marketing & Communications Assistant at The Jewish Federation in the Heart of New Jersey. He recently returned from his Birthright trip to Israel (read blog #1) and extended travels to Eastern Europe. This is his second blog about his travels in Poland.

My Grandparents grew up in Czestochowa – a small, yet well-known city in southern Poland. It is one of the most important pilgrimage sites for Polish Catholic, being the home of the Black Madonna in addition to over 50 Catholic churches. Prior to World War II, Jews made up a fifth of the area’s population. But being so close to the border had its consequences: it was one of the first places to quickly fall victim to the German offensive. After enduring the brutal Nazi-occupation for nearly five years, my Grandfather and Grandmother were the only survivors from their respective families in 1945. They vowed never to return to Poland. In November, I decided to visit.

It was cloudy and bright gray all morning. I was lucky enough to be accompanied by my girlfriend, who had met me in Israel after Birthright. We had gone from Tel Aviv to Budapest and now to Poland. We rode the train for two hours, seeing rural Poland along the way. A Poland that was synonymous with “the old country;” comprised of vast hills, farm animals, and small, colorful houses spread throughout the fields. “The old country.”

The girl at the front desk of our hostel was taken back when I asked for a train schedule to Czestochowa. “Aside from religious Polish people, I’ve never heard of foreigners visiting that city,” she proclaimed. I explained to her I was neither Catholic nor looking for some religious enlightenment, but rather I was on a personal journey to my family’s historical roots. As the half-empty train approached Czestochowa, the blue sky began to peek through the clouds and, before we knew it, the sun was out as we came to a screeching halt.

Prior to leaving New Jersey, my 94-year-old Grandmother gave me the address of her childhood home. The last time she was there was in 1945 after the war as a young, distraught twenty something. On a napkin, without hesitation, she drew an impromptu map of her neighborhood. From the train station, she indicated that her apartment building was only a block away. Katedralna 7 was her address (she even spelled it right). I was in awe as she vividly remembered her neighborhood from 75 years before. “There was a market in my building and a bakery across the street,” she described as she pointed poignantly in the air with her eyes closed. It was incredible to witness. I took her information and confirmed it with a map online. I showed her a street view of the building now in present-day to verify it was still standing. That was enough to make her cry.

After getting off the train, I knew exactly where to go. I first recognized the street name next to the train station, knowing it was the location my Grandfather had described where Jews were routinely loaded into cattle cars and sent to a mysterious location, later found out to be Treblinka. One block away was Katedralna. The experience quickly became surreal. I soon found myself in the courtyard of her apartment building. I stood there, mostly in silence, taking it all in while imagining the neighborhood bustling with life. Unfortunately, I had no knowledge of what actual apartment my Grandma had lived in, but seeing the building was equally significant.

Around the corner was a huge church, one of the biggest I had ever seen. I immediately recognized the church, not by its immaculate size, but by its significance in the story of my Grandparents. This was where Germans had rounded up Jews on September 3, 1939 - “Bloody Monday.” My Grandfather, then 18 years old, was rounded up with his brother and father and detained in the church. This is the church where Jews were kept for days and routinely shot at with machine guns. I had heard this story, but standing there, trying to imagine the terror endured, was surreal. I can still hear my Grandfather’s voice telling the story, describing his father jumping on top of him and his brother to shield the bullets. That was the first of many assaults they encountered.

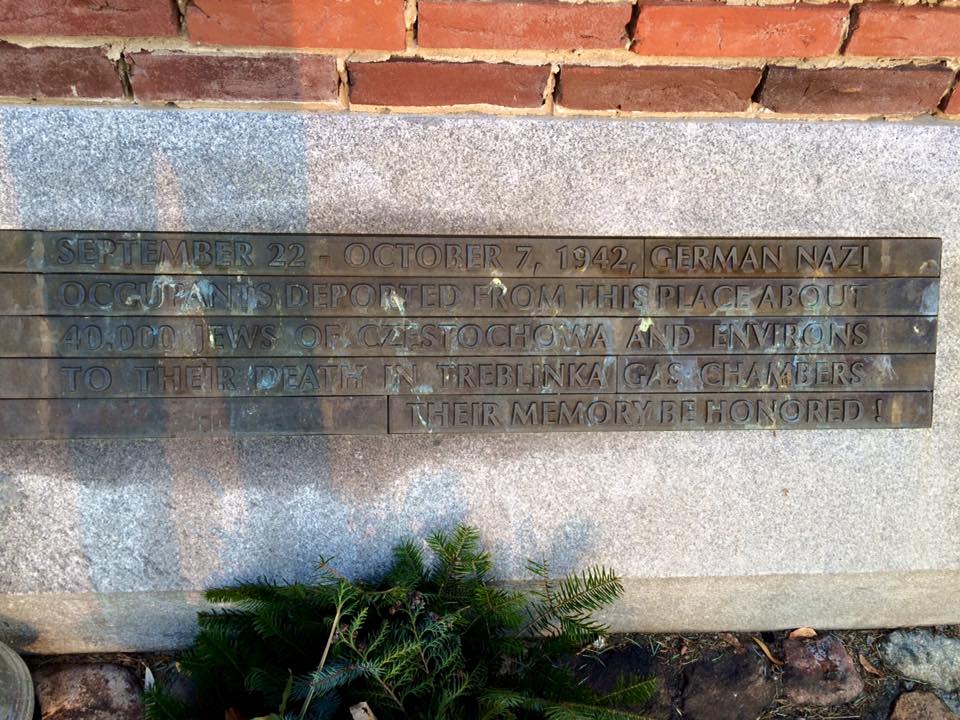

As we continued our walk through the neighborhood, we came across a large memorial dedicated to the Jews of Czestochowa. The brick monument resembled a ghetto wall and stood in the exact spot where daily round ups and deportations took place. Accompanying the wall was a plaque which read “September 22-October 7, 1942, German Nazi occupants deported from this place about 40,000 Jews of Czestochowa and environs to their death in Treblinka gas chambers. Their memory be honored!”

I stood at the memorial and was overcome by an existential force. After a minute of standing there, tears flowed uncontrollably. I thought about my own existence, my life and the experiences I call mine. This was the spot where my then 17-year-old Grandmother was separated from her parents and three brothers, and where she became completely alone, aside from having my Grandfather at her side (he himself only 18). I thought about my entire family’s existence – aunts and uncles and cousins and their children - and the fact that they all stem from my two Grandparents. Had either of them perished, my family would have simply ceased to exist. By something that can only be deemed a miracle, they survived 6 years of hell while their friends and families were murdered by the hands of the Nazis and their associates. I thought about all of their relatives who perished and imagined how big my family would be today had they all survived. But most of all, I realized just how amazing it is to be alive and how grateful I truly am to wake up every day. At that moment, I was extremely proud to be Jewish. I recognize that my existence is a way to prove the efforts of those who sought to destroy human life based on simple differences unsuccessful. Visiting Czestochowa was, in fact, a birthright. It is an experience that will stay with me forever.

0Comments

Add CommentPlease login to leave a comment